Leandro Locsin, hailed as a National Artist since 1990, was a creative genius whose architectural legacy remains unparalleled. Every structure he designed bore his distinctive touch, characterized by floating volumes and a delicate balance between lightness and massiveness.

Throughout his illustrious career spanning from 1955 until his passing in 1994, Locsin left an indelible mark with a staggering portfolio of 75 residences and 88 buildings. Among his creations were 11 churches, 23 public edifices, 48 commercial complexes, six grand hotels, and even an airport terminal.

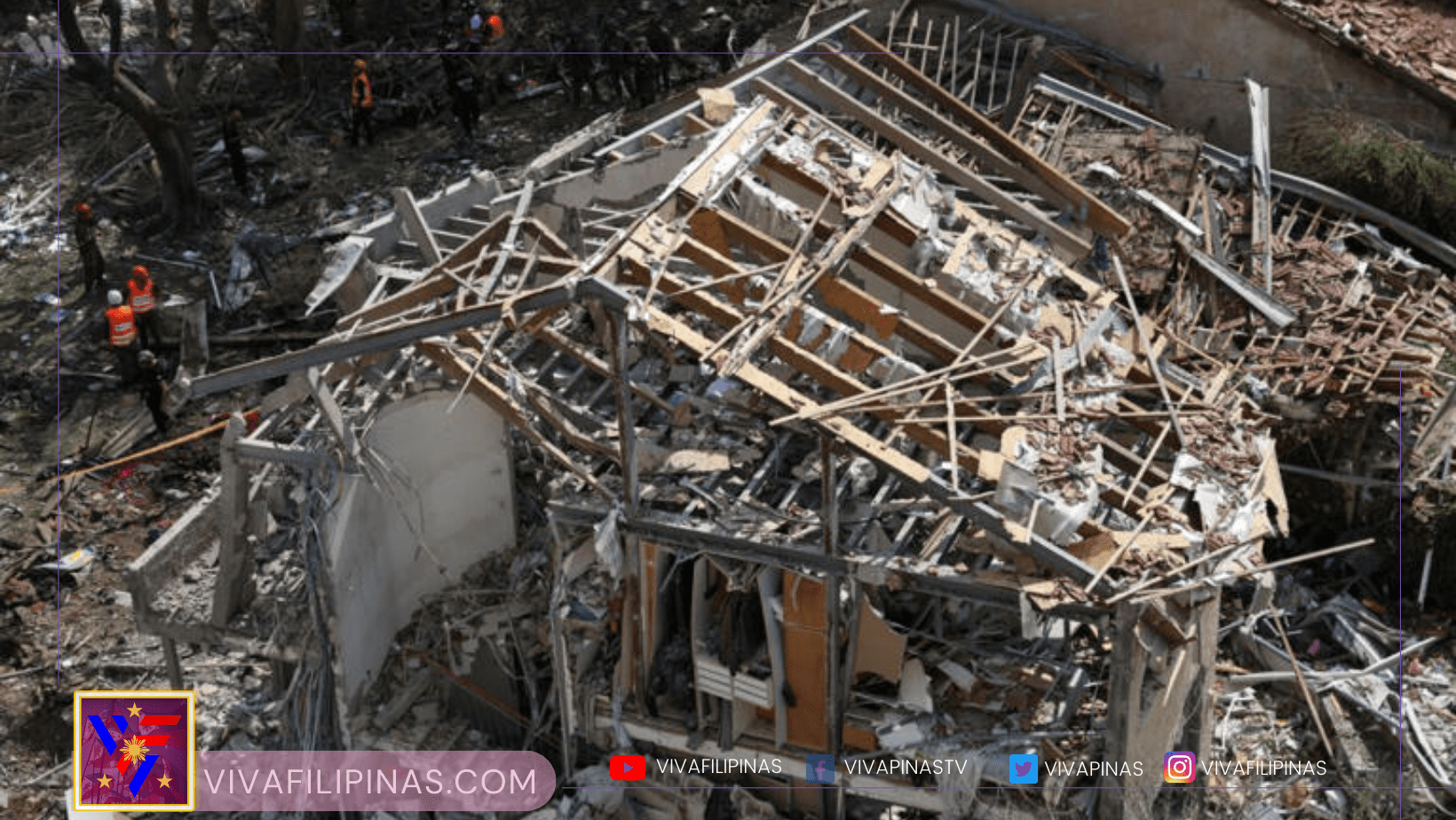

Greenbelt 1, now facing demolition, is just a fragment of Locsin’s architectural marvels scattered across Makati. This bustling city, particularly along Ayala Avenue and its central business district, boasts perhaps the densest concentration of Locsin’s masterpieces. Many of these are exclusive homes tucked away within gated communities, serving as testaments to his enduring legacy.

The close relationship between Locsin and Fernando Zobel may shed light on Makati’s abundance of his works. Locsin’s stint as an artist-draftsman for Ayala Corporation during his architectural studies cemented his ties to the city. Juggling work and classes, Locsin honed his craft while contributing to Ayala’s burgeoning urban landscape.

Accompanied by Zobel, Locsin embarked on a transformative journey to Japan in 1956, a pivotal experience that broadened his architectural horizons. Immersed in Japanese design principles, he was captivated by the modular approach, the harmonious scale, and the authentic use of materials that celebrated their inherent colors and textures.

The 1960s marked Locsin’s meteoric rise to prominence, as he secured significant commercial and governmental commissions. According to Karl Castro, co-founder of Brutalist Pilipinas, this era saw Locsin garnering widespread recognition, establishing himself as a luminary in the architectural landscape.

During this time, Joseph McMicking, then CEO of Ayala Corporation, spearheaded the master planning of Makati. This period, spanning from the late 1940s to the 1970s, coincided with Locsin’s prime, intertwining his illustrious career with the formative years of the Makati Central Business District (CBD).

Leandro Locsin’s transformative journey to Japan sparked the design brilliance behind Monterrey Apartments, the pioneering luxury residence on Ayala Avenue completed in 1957. This landmark set the bar for subsequent developments along this prestigious avenue, marking the genesis of a series of Locsin-designed projects that would shape Makati’s skyline. Ayala Building I (Elizalde Building) in 1958, Ayala Building II (Filipinas Life Assurance Corporation) in 1959, and numerous residences followed suit, each bearing Locsin’s signature style.

However, Monterrey Apartments’ demise in the 1990s foreshadowed a pattern of demolition that befell many Locsin structures. Notable casualties include the Mandarin Oriental in 2014 and the InterContinental Manila in 2016, making room for new urban landscapes like OneAyala development. Even the Chapel of St. Alphonsus Ligouri in Magallanes Village, built in 1970, succumbed to fire in 2004 and was later rebuilt by another architect in 2007.

This trend reflects a broader trend of undervaluing Brutalist architecture. The renovation of the original Ayala Museum building in 2002, designed by Locsin and replaced with a modernist structure by his son, marked the beginning of this depreciation. Associated with the Marcos regime’s architectural preferences, Brutalism faced criticism for its perceived coldness and datedness.

While Locsin’s iconic landmarks like the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the Philippine International Convention Center underscored his architectural prowess, his commercial and minor Brutalist buildings often faced unfair comparisons and neglect. The lack of appreciation for modernist heritage, coupled with lax heritage laws, facilitated the demolition of these structures.

This disregard for modernist heritage has emboldened owners to pursue renovations and redevelopment, exploiting legal loopholes to dismantle these cultural icons. The ineffectiveness of heritage laws is evident in the continued demolition of Locsin buildings in Makati, perpetuating a cycle of destruction and loss.

The demolition of the BDO Corporate Center, formerly known as the Philippine Commercial International Bank Towers in 2022, sparked controversy when the NCCA initially attempted to halt the process. However, by the time the intervention occurred, the property was already halfway dismantled.

In the same year, Philippine Long Distance Telephone (PLDT) Inc., owners of the Ramon Cojuangco Building designed by Locsin in 1982, petitioned the NCCA to remove its status as an important cultural property. They argued that the building lacked distinctiveness and historical significance, and did not align with Locsin’s style.

Architectural heritage advocates, including Karl Castro and the team behind Brutalist Pilipinas, successfully intervened to temporarily halt the demolition of the Ramon Cojuangco Building. Despite this victory, the fate of the structure remains uncertain amidst plans for a modern headquarters.

The threat to architectural heritage extends beyond Locsin’s buildings in Makati. Structures by lesser-known Filipino architects, such as Carlos Arguelles, face even greater vulnerability due to their lack of legal protection and recognition.

The struggle between preserving cultural heritage and pursuing profitable ventures underscores the dilemma faced by building owners and developers. Many aging structures require updates to meet modern standards or are deemed unprofitable in prime locations, leading to their potential demolition.

The SSS Makati Building, a collaboration between National Artists Ildefonso Santos and Leandro Locsin, stands as a poignant example of neglected architectural heritage awaiting its inevitable fate.

View this post on Instagram

As successive demolitions reshape the cityscape, the cycle of destruction and renewal perpetuates the myth of Makati as a thriving metropolis. Historian Ambeth Ocampo’s reflection on the Ayala Museum’s transformation encapsulates this sentiment, highlighting the tension between commercialization and heritage preservation in urban development.

In the face of rapid urbanization, the challenge lies in finding a balance between honoring the past and embracing the future, ensuring that each architectural relic tells a story of resilience and adaptation in the ever-evolving cityscape.